Se afișează postările cu eticheta Grecia. Afișați toate postările

Se afișează postările cu eticheta Grecia. Afișați toate postările

luni, 8 februarie 2021

Arhitectura Greciei antice

https://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Architecture/

Greek Architecture

Definition

published on 06 January 2013

Greek architects provided some of the finest and most distinctive buildings in the entire Ancient World and some of their structures, such as temples, theatres, and stadia, would become staple features of towns and cities from antiquity onwards. In addition, the Greek concern with simplicity, proportion, perspective, and harmony in their buildings would go on to greatly influence architects in the Roman world and provide the foundation for the classical architectural orders which would dominate the western world from the Renaissance to the present day.

The Architectural Orders

There are five orders of classical architecture - Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Tuscan, and Composite - all named as such in later Roman times. Greek architects created the first three and hugely influenced the latter two which were composites rather than genuine innovations. An order, properly speaking, is a combination of a certain style of column with or without a base and an entablature (what the column supports: the architrave, frieze, and cornice). The earlier use of wooden pillars eventually evolved into the Doric column in stone. This was a vertical fluted column shaft, thinner at its top, with no base and a simple capital below a square abacus. The entablature frieze carried alternating triglyphs and metopes. The Ionic order, with origins in mid-6th century BCE Asia Minor, added a base and volute, or scroll capital, to a slimmer, straighter column. The Ionic entablature often carries a frieze with richly carved sculpture. The Corinthian column, invented in Athens in the 5th century BCE, is similar to the Ionic but topped by a more decorative capital of stylized acanthus and fern leaves. These orders became the basic grammar of western architecture and it is difficult to walk in any modern city and not see examples of them in one form or another.

Materials

The Greeks certainly had a preference for marble, at least for their public buildings. Initially, though, wood would have been used for not only such basic architectural elements as columns but the entire buildings themselves. Early 8th century BCE temples were so constructed and had thatch roofs. From the late 7th century BCE, temples, in particular, slowly began to be converted into more durable stone edifices; some even had a mix of the two materials. Some scholars have argued that certain decorative features of stone column capitals and elements of the entablature evolved from the skills of the carpenter displayed in more ancient, wooden architectural elements.

The stone of choice was either limestone protected by a layer of marble dust stucco or even better, pure white marble. Also, carved stone was often polished with chamois to provide resistance to water and give a bright finish. The best marble came from Naxos, Paros, and Mt. Pentelicon near Athens.

Temples, Treasuries & Stoas

ARCHITECTS USED SOPHISTICATED GEOMETRY AND OPTICAL TRICKS TO PRESENT BUILDINGS AS PERFECTLY STRAIGHT AND HARMONIOUS.

The ancient Greeks are rightly famous for their magnificent Doric and Ionic temples, and the example par excellence is undoubtedly the Parthenon of Athens. Built in the mid 5th century BCE in order to house the gigantic statue of Athena and to advertise to the world the glory of Athens, it still stands majestically on the city's acropolis. Other celebrated examples are the massive Temple of Zeus at Olympia (completed c. 460 BCE), the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (completed c. 430 BCE), which was considered one of the wonders of the ancient world, and the evocative Temple of Poseidon at Sounion (444-440 BCE), perched on the cliffs overlooking the Aegean. The latter is illustrative of the Greek desire that such public buildings should not just fulfil their typical function of housing a statue of a Greek deity, and not only should they be admired from close-up or from the inside, but also that they should be admired from afar. A great deal of effort was made to build temples in prominent positions and, using sophisticated geometry, architects included optical 'tricks' such as thickening the lower parts of columns, thickening corner columns, and having columns ever so slightly lean inwards so that from a distance the building seemed perfectly straight and in harmony. Many of these refinements are invisible to the naked eye, and even today only sophisticated measuring devices can detect the minute differences in angles and dimensions. Such refinements indicate that Greek temples were, therefore, not only functional structures but also that the building itself, as a whole, was symbolic and an important element in the civic landscape.

Greek temples, at least on the mainland, followed a remarkably similar plan and almost all were rectangular and peripteral, that is their exterior sides and façades consisted of rows of columns. Notable exceptions included the magnificently eccentric Erechtheion of Athens with its innovative Caryatid columns and the temples of the Cyclades which, although still Doric, only had columns on the front façade (prostyle), which was often wider than the length of the building. So too, temples from Ionia tended to differ from the norm, usually having a double colonnade (dipteral). However, returning to the standard Greek temple layout, the rectangular peristyle of columns (8 x 17 in the case of the Parthenon, 6 x 13 for the temple of Zeus at Olympia) surrounded an inner chamber or cella with the whole standing on a stepped platform or stylobate and the interior paved with rectangular slabs. The roof was usually raised along a central ridge with a slope of approximately 15 degrees and was constructed from wooden beams and rafters covered in overlapping terracotta or marble tiles. Decorative acroteria (palms or statues) often stood at each point of the pediment. Finally, the doors to temples were made of wood (elm or cypress) and often decorated with bronze medallions and bosses.

Many temples also carried architectural sculpture arranged to tell a narrative. Pediments, friezes, and metopes all carried sculpture, often in the round or in high relief and always richly decorated (with paint and bronze additions), which retold stories from Greek mythology or great episodes in that particular city's history.

Temples also indicate that Greek architects (architektones) were perfectly aware of the problems of providing stable foundations able to support large buildings. Correct water drainage and the use of continuous bases on foundations above various layers of fill material (conglomerate soft rocks, soil, marble chips, charcoal, and even sheepskins) allowed large Greek buildings to be built in the best positions regardless of terrain and to withstand the rigours of weather and earthquake over centuries. Indeed, absolute stability was essential, as even a slight settling or subsidence in any part of the building would render useless the optical refinements discussed above. It is remarkable that the vast majority of Greek buildings that have collapsed have done so only because of human intervention - removing blocks or metal fixtures for reuse elsewhere - weakening the overall structure. Structures not interfered with, such as the Temple of Hephaistos in the Athens agora, are testimony to the impressive durability of Greek buildings.

Other structures which were constructed near temples were monumental entrance gates (such as the Propylaia of Athens' acropolis) and small buildings to house dedications, often from specific city-states. These very often borrowed architectural elements from the temple such as columned façades and friezes. An excellent example is the Treasury of the Athenians at Delphi (490 BCE).

The stoa was another structure common to many temple complexes from the 7th century BCE onwards. This was a long, narrow row of columns backed by a plain wall and roofed. Often placed at right-angles to create an enclosed open space, stoas were used for all manner of purposes such as meeting places and storage. The agora or market place of many ancient Greek towns would be composed of a large open square surrounded by a stoa. One unusual stoa is that of the Sicilian colony of Selinus. This was constructed between 580 and 570 BCE and was a trapezoid in shape. More interestingly, the nearby shops all present the same façade despite being different types of buildings. This is evidence that there was some sort of centrally controlled planning authority which ensured harmony of architecture in important public places. Certainly, during the 5th century BCE there were professional town planners, the most famous of which was Hippodamos who is often credited with planning the Piraeus and Rhodes. Interestingly, there is very often a correspondence between architectural changes in towns and changes in political regime. One final function of the stoa in Hellenistic times was in the gymnasium and palaistra complexes, notably at the great sanctuaries of Olympia, Delphi, and Nemea. These stoas were used to create an enclosed space for physical exercise and provide a practice area for such field events as the javelin and discus.

Support our Non-Profit Organization

With your help we create free content that helps millions of people learn history all around the world.BECOME A MEMBER

Temples, treasuries, and stoas then, with their various orders and arrangements of columns have provided the most tangible architectural legacy from the Greek world, and it is perhaps ironic that the architecture of Greek religious buildings has been so widely adopted in the modern world for such secular buildings as court houses and government buildings.

The Theatre

Another distinctive Greek contribution to world culture was the amphitheatre. The oldest certain archaeological evidence of theatres dates from the late 6th century BCE but we may assume that Greeks gathered in specified public places much earlier. Indeed, Bronze Age Minoan sites such as Phaistos had large stepped-courts which are thought to have been used for spectacles such as religious processions and bull-leaping sports. Then from the late 6th century BCE we have a rectangular theatre-like structure from Thorikos in Attica which had a temple dedicated to Dionysos at one end. This would suggest it was used during Dionyistic festivals, at which dramas were often presented. However, it was from the 5th century BCE that the Greek amphitheatre took on its recognisable and most influential form. This was an open-air and approximately semi-circular arrangement of rising rows of seats (theotron) which provided excellent acoustics. The stage or orchestra was also semi-circular and backed by a screen or skene, which would become more and more monumental in the following centuries. Monumental arches often provided the entrances (paradoi) on either side of the stage.

Examples abound throughout the Greek world and many theatres have survived remarkably well. One of the most celebrated is the theatre of Dionysus Eleutherius on the southern slope of Athens' acropolis where the great plays of Sophocles, Euripedes, Aeschylus, and Aristophanes were first performed. One of the largest is the theatre of Argos which had a capacity for 20,000 spectators, and one of the best preserved is the theatre of Epidaurus which continues every summer to host major dramatic performances. Theatres were used not only for the presentation of plays but also hosted poetry recitals and musical competitions.

The Stadium

Another lasting Greek architectural contribution to world culture was the stadium. Stadiums were named after the distance (600 ancient feet or around 180 metres) of the foot-race they originally hosted - the stade or stadion. Initially constructed near natural embankments, stadia evolved into more sophisticated structures with rows of stone or even marble steps for seating which had divisions for ease of access. Conduits ran around the track to drain off excess rainfall and in Hellenistic times vaulted corridors provided a dramatic entrance for athletes and judges. Famous examples include those at Nemea and Olympia which had seating capacities of 30,000 and 45,000 spectators respectively.

Housing

Considering more modest structures, there were fountain houses (from the 6th century BCE) where people could easily collect water and perhaps, as black-figure pottery scenes suggest, socialise. Regarding private homes, these were usually constructed with mud brick, had packed earth floors, and were built to no particular design. One- or two-storied houses were the norm. Later, from the 5th century BCE, better houses were built in stone, usually with plastered exterior and frescoed interior walls. Also, there was often no particular effort at town planning which usually resulted in a maze of narrow chaotic streets, even in such great cities as Athens. Colonies in Magna Graecia, as we have seen in Selinus, were something of an exception and often had more regular street plans, no doubt a benefit of constructing a town from scratch.

In conclusion then, we may say that ancient Greek architecture has provided not only many of the staple features of modern western architecture, but it has also given the world truly magnificent buildings which have literally stood the test of time and continue to inspire admiration and awe. Many of these buildings - the Parthenon, the Caryatid porch of the Erechtheion, the volute of an Ionic capital to name just three - have become the instantly recognisable and iconic symbols of ancient Greece.

Bibliography

miercuri, 30 decembrie 2020

Istorici greci

ISTORICI GRECI DIN ANTICHITATE

Herodot (484 BC - 425 BC)

Fragment d'Hérodote, papyrus d'Oxyrhynque

Ἡροδότου Ἁλικαρνησσέος ἱστορίης ἀπόδεξις ἥδε, ὡς μήτε τὰ γενόμενα ἐξ ἀνθρώπων τῷ χρόνῳ ἐξίτηλα γένηται, μήτε ἔργα μεγάλα τε καὶ θωμαστά, τὰ μὲν Ἕλλησι τὰ δὲ βαρϐάροισι ἀποδεχθέντα, ἀκλεᾶ γένηται, τά τε ἄλλα καὶ δι' ἣν αἰτίην ἐπολέμησαν ἀλλήλοισι. ================================ | « Hérodote d'Halicarnasse présente ici les résultats de son Enquête afin que le temps n'abolisse pas le souvenir des actions des hommes et que les grands exploits accomplis soit par les Grecs, soit par les Barbares, ne tombent pas dans l'oubli ; il donne aussi la raison du conflit qui mit ces deux peuples aux prises. » ======================================= |

15 Ancient Greek Historians And How They’ve Shaped Ancient History

The Ancient Greeks created history as a way to record, study, and understand the past. These are the fifteen most important Ancient Greek Historians and their works.

August 20, 2020

Harris Homer Roll, 1st-2nd century, via The British Library, London (background); with

Seated Man Writing, 525-475 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (foreground)

During Classical Antiquity, the ancient Greeks developed the discipline that we today know as history. Ancient Greek Historians composed their works by interviewing eyewitnesses, studying documents, and drawing on earlier historical research. Some ancient Greek Historians even actively participated in or witnessed the events they described themselves. With the passage of time, the writings of many ancient Greek Historians have been lost; it exists only as fragments, quotations, or references in later works. Regardless of whether or not their work has survived in its entirety, the Ancient Greek Historians shaped our understanding of Classical Antiquity and the study of history.

Ancient Greek Historians And Fathers Of History

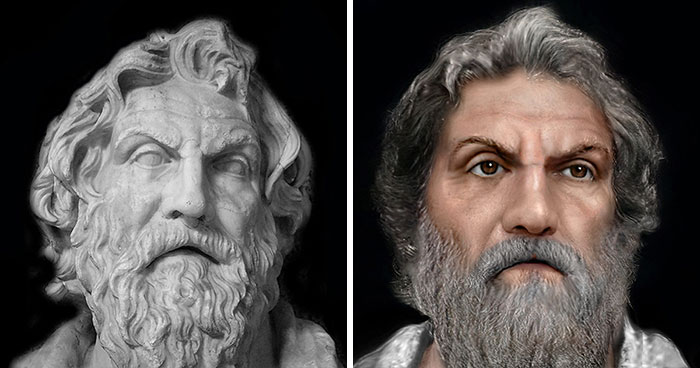

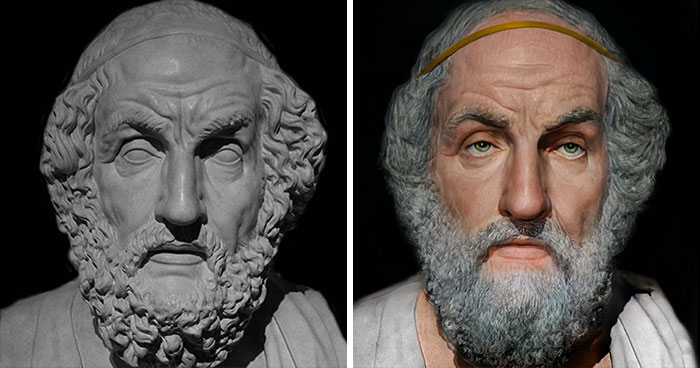

Homer  Roman Bust of Homer, 2nd century BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Ostrakon with Coptic lines from Homer’s Iliad, 580-640 AD, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Roman Bust of Homer, 2nd century BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Ostrakon with Coptic lines from Homer’s Iliad, 580-640 AD, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Roman Bust of Homer, 2nd century BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Ostrakon with Coptic lines from Homer’s Iliad, 580-640 AD, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Roman Bust of Homer, 2nd century BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Ostrakon with Coptic lines from Homer’s Iliad, 580-640 AD, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)Almost nothing is known of Homer, the legendary author of the Iliad and Odyssey; epic poems which tell the story of the Trojan War and its aftermath. Homer’s identity, the period during which he lived, and the circumstances in which he composed these poems have been hotly debated for centuries. Some even go so far as to question his very existence. What cannot be questioned is the influence that his works have had on Western Historiography and the development of history in Ancient Greece.

During Antiquity, the Trojan War was the first “historical event” to be recorded in Ancient Greece and became foundational. Homer’s works were widely read and were incorporated into the educational systems of many schools of philosophy. As a result, numerous Greek historians drew inspiration from Homer when they composed their own histories. The Trojan War also served as a beginning point for ancient Greek historians as it was often the earliest event that they had any knowledge of and its heroes were tied to the foundational myths and legends of various tribes, dynasties, cities, regions, and kingdoms. Some, however, criticized Homer for his treatment of the gods and doubted his version of the events of the Trojan War; though they all tended to accept that it had happened.

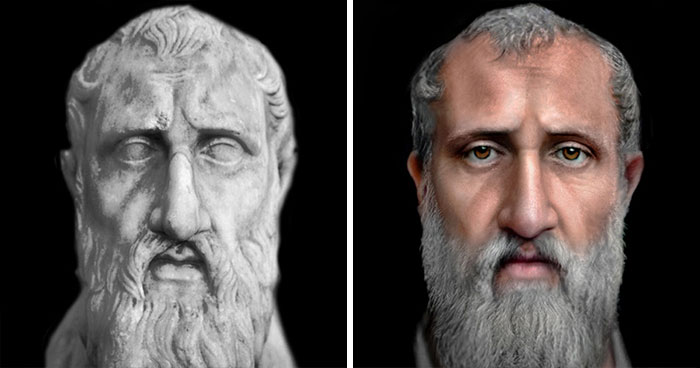

Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC)

Roman Marble Bust of Herodotus, 2nd century, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left);

with Book Illustration for The Histories of Herodotus by Anton Woensam & Eucharius Hirtzhorn, 1526, via The British Museum, London (right)

Herodotus, the so-called “Father of History,” was born in the Greek city of Halicarnassus which was then part of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. For reasons that are unclear, but were perhaps motivated by local politics, Herodotus traveled extensively throughout the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean and is known to have visited Samos, Egypt, Tyre, Babylon, Athens, Magna Graecia, and Macedonia. His great work, The Histories, was conceived as an attempt to explain the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars. This work, which begins in the mythical period, focuses the years between 550-479 BC and spans 9 books

Herodotus included a wealth of information in The Histories and has a tendency towards long digressions on anthropological and ethnographic matters. Although his work inspired many later historians, Herodotus himself remains controversial and has been called the “Father of Lies.” His work contains many legendary and fanciful accounts which later historians accused him of making up for entertainment value. However, Herodotus himself states that he merely reports what he has been told and even notes when he does not believe his source. Today, a number of the more fanciful aspects of The Histories, such as the Amazons, have been confirmed through archaeology.

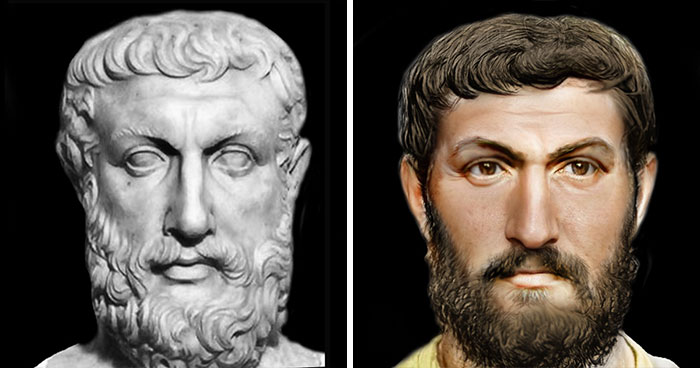

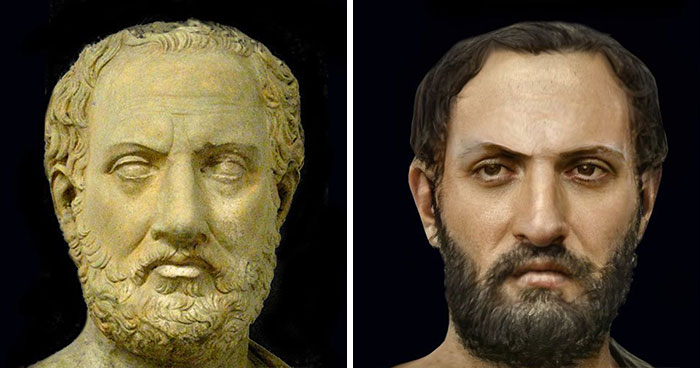

Thucydides (c. 460-400 BC) Portrait Head of Thucydides, 2nd Century AD, via The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (left); with ‘Thucidides…von dem…Peloponnenser kreig’ book in German by Jorg Breu I, Jorg Breu II, and Hans Schaufelein, 1533, via The British Museum, London

Portrait Head of Thucydides, 2nd Century AD, via The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (left); with ‘Thucidides…von dem…Peloponnenser kreig’ book in German by Jorg Breu I, Jorg Breu II, and Hans Schaufelein, 1533, via The British Museum, London

Portrait Head of Thucydides, 2nd Century AD, via The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (left); with ‘Thucidides…von dem…Peloponnenser kreig’ book in German by Jorg Breu I, Jorg Breu II, and Hans Schaufelein, 1533, via The British Museum, London

Portrait Head of Thucydides, 2nd Century AD, via The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (left); with ‘Thucidides…von dem…Peloponnenser kreig’ book in German by Jorg Breu I, Jorg Breu II, and Hans Schaufelein, 1533, via The British Museum, LondonA well connected Athenian aristocrat, Thucydides owned a gold mine, served as a general during the Peloponnesian War, survived the Plague of Athens, and was eventually exiled from Athens for the failure of a military campaign in Thrace. He is best known for his History, which is today commonly rendered as The History of the Peloponnesian War. This work spans 8 books and describes the events of a period that roughly encompasses 438-411 BC. As the work ends rather abruptly, it is believed that Thucydides died suddenly and unexpectedly.

Thucydides is, along with Herodotus, regarded as the “Father of History;” his more scientific approach which did not acknowledge divine intervention, along with his non-judgmental style which sought to report events in an unbiased manner, has led to him also being regarded as the first “true historian.” However, he also freely acknowledges making up appropriate speeches for the figures in his History, based on what he felt that they ought to have said. Nevertheless, Thucydides’ influence on later ancient Greek historians and Western Historiography was enormous.

Ancient Greek Historians Become Professionals

Xenophon (c. 430-354 BC) Portrait of Xenophon by John Chapman & J. Wilkes, 1807, via The British Museum, London (left); with Xenophon’s Hellenica, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)

Portrait of Xenophon by John Chapman & J. Wilkes, 1807, via The British Museum, London (left); with Xenophon’s Hellenica, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)

Portrait of Xenophon by John Chapman & J. Wilkes, 1807, via The British Museum, London (left); with Xenophon’s Hellenica, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)

Portrait of Xenophon by John Chapman & J. Wilkes, 1807, via The British Museum, London (left); with Xenophon’s Hellenica, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)Born in Athens, Xenophon was an ancient Greek historian, soldier, and philosopher who marched an army of 10,000 Greek mercenaries out of Persia, associated with Socrates and Plato, and had close ties to Sparta. His work as a historian reflects his experiences as it includes: The Anabasis, which details the March of the 10,000; The Cyropaedia, which describes the early life of Cyrus the Great; Agesilaus, a biography of Agesilaus II a powerful king of Sparta; and Polity of the Lacedaemonians, a history of Sparta and its institutions.

Xenophon’s most important work, however, was the Hellenica or “writings on Greek subjects,” which covers the years 411-362 BC and spans a total of 7 books. This history picked up where Thucydides left off and was primarily intended to be read by Xenophon’s friends, who had participated in the events describes. As such, the Hellenica literally begins after Thucydides’ final sentence. Overall, the Hellenica was for Xenophon a deeply personal project and although he follows Thucydides stylistically his pro-Spartan and anti-democracy bias is noticeable.

Ctesias (5th Century BC) Artaxerxes II, King of Persia published by Gerard de Jode, 1585, via The British Museum, London (left); with Attic Red-Figure Aryballos depicting a Greek Physician treating a Patient, 480-70 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (right)

Artaxerxes II, King of Persia published by Gerard de Jode, 1585, via The British Museum, London (left); with Attic Red-Figure Aryballos depicting a Greek Physician treating a Patient, 480-70 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (right)

Artaxerxes II, King of Persia published by Gerard de Jode, 1585, via The British Museum, London (left); with Attic Red-Figure Aryballos depicting a Greek Physician treating a Patient, 480-70 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (right)

Artaxerxes II, King of Persia published by Gerard de Jode, 1585, via The British Museum, London (left); with Attic Red-Figure Aryballos depicting a Greek Physician treating a Patient, 480-70 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (right) Ctesias was a Greek living in Cnidus, a Carian city in Anatolia, this ancient Greek Historian lived under the Achaemenid Empire. A royal physician to the Achaemenid king Artaxerxes II, he accompanied the king on various expeditions and treated his wounds. Ctesias had access to the royal archives of the Achaemenid Empire, which he drew upon to construct his histories.

He is known for two works, the Persica and the Indica. The Indica reflects Achaemenid knowledge and beliefs about India and is known only as fragments and quotations preserved in the works of other historians. Ctesias’ other work, the Persica, spanned 23 books and was originally written in opposition to Herodotus and his account. The Persica was highly valued and widely quoted in antiquity, although even then there were doubts about its reliability.

Theopompus (c. 380-318 BC) Tetradrachm of Philip II, 355-48 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Terracotta of an Old Man teaching a Boy to Write, late 4th century, via The British Museum, London (right)

Tetradrachm of Philip II, 355-48 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Terracotta of an Old Man teaching a Boy to Write, late 4th century, via The British Museum, London (right)

Tetradrachm of Philip II, 355-48 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Terracotta of an Old Man teaching a Boy to Write, late 4th century, via The British Museum, London (right)

Tetradrachm of Philip II, 355-48 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Terracotta of an Old Man teaching a Boy to Write, late 4th century, via The British Museum, London (right)Theopompus was born on the island of Chios, this ancient Greek Historian spent time in Athens after his father was exiled where he studied rhetoric and built a network of contacts. With the support of Alexander the Great, he was able to return to Chios, but was again exiled and went to the court of Ptolemaic Egypt. With his training, contacts, and relative wealth, Theopompus was well equipped to be a historian.

His chief works were the Hellenica, which deals with the history of Greece from 411-394 BC, and the Philippica, which describes the reign of Philip II. Both works are known as fragments but the Philippica was widely quoted by later historians. Theopompus was also criticized for his lengthy digressions, love of incredible or romantic stories, and the lengths he would go to in censuring his subjects for what he perceived as their failings.

Cleitarchus (c. mid-late 4th Century BC) Drachm of Alexander the Great, 328-20 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver coin depicting Ptolemy I Soter, 323-284 BC, via The British Museum, London (right)

Drachm of Alexander the Great, 328-20 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver coin depicting Ptolemy I Soter, 323-284 BC, via The British Museum, London (right)

Drachm of Alexander the Great, 328-20 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver coin depicting Ptolemy I Soter, 323-284 BC, via The British Museum, London (right)

Drachm of Alexander the Great, 328-20 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver coin depicting Ptolemy I Soter, 323-284 BC, via The British Museum, London (right)Cleitarchus was one of the earliest ancient Greek historians of Alexander the Great, he may have even accompanied the Macedonian army during its campaigns. Later he remained active at the court of Ptolemy I Soter, founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. As such, he was able to witness first hand or access witnesses to the events he described. His only known work, the History of Alexander, has survived in the form of thirty fragments.

Cleitarchus’ work, though now lost, was very popular during Antiquity and was widely read; it was the most famous history of Alexander the Great. Many later historians, such as Plutarch, Aelian, Strabo, Quintus Curtius, and Justin quote it in their works. It also served to inspire what became known as the Alexander Romances. However, it also received its share of criticism for Cleitarchus’ exaggerated writing style, which impinged on its trustworthiness.

Marsyas of Pella (c. 356-294 BC) Silver Tetradrachm of Demetrius Poliocretes, 289-88 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Marble Head of a Youth with a horned diadem, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Silver Tetradrachm of Demetrius Poliocretes, 289-88 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Marble Head of a Youth with a horned diadem, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Silver Tetradrachm of Demetrius Poliocretes, 289-88 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Marble Head of a Youth with a horned diadem, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Silver Tetradrachm of Demetrius Poliocretes, 289-88 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Marble Head of a Youth with a horned diadem, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)Marsyas was a Macedonian of noble birth, this ancient Greek historian appears to have been a relative of Antigonus I Monophthalmus (One-Eyed), a general of Alexander the Great’s who ruled large parts of Asia. It appears that Marsyas and Antigonus were stepbrothers. Later, Marsyas commanded a division of Demetrius Poliocretes’ (The Besieger) fleet at the Battle of Salamis in 306 BC. No mere armchair historian, Marsyas took an active role in public affairs.

His major work was the Makedonika which consisted of 10 books and described the history of Macedonia from the earliest times to about 331 BC. This work was repeatedly cited by later Roman and Byzantine authors. He is also credited with writing a history of Alexander the Great’s education, and possibly a treatise on the antiquities of Athens

Duris of Samos (c. 350-281 BC) Fragment of a Samian amphora with maker’s mark, 350-00 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Portrait of Alcibiades, 1775-1800, via The British Museum, London (right)

Fragment of a Samian amphora with maker’s mark, 350-00 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Portrait of Alcibiades, 1775-1800, via The British Museum, London (right)

Fragment of a Samian amphora with maker’s mark, 350-00 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Portrait of Alcibiades, 1775-1800, via The British Museum, London (right)

Fragment of a Samian amphora with maker’s mark, 350-00 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Portrait of Alcibiades, 1775-1800, via The British Museum, London (right)Claiming descent from the infamous Alcibiades of Athens, Duris was an ancient Greek historian and at some point the tyrant of Samos. His main work was the Histories (also known as Macedonica and Hellenica), which describes the history of Greece and Macedonia from 371-281 BC. His narrative was continued by the later historian Phylarchus.

Duris was an exemplar of “tragic history,” a new style or school of historical writing which placed a greater value on entertainment and excitement rather than factual reporting. During Antiquity, few later historians praised Duris; disparaging his style, his composition, and doubting his trustworthiness. However, many still utilized his work. Today, his historical work is known only in fragments and includes his Histories, On Agathocles, and the Annals of Samos.

Timaeus (c. 345-250 BC) Limestone Funerary Relief, 325-00 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Terracotta Vase, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Limestone Funerary Relief, 325-00 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Terracotta Vase, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Limestone Funerary Relief, 325-00 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Terracotta Vase, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Limestone Funerary Relief, 325-00 BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (left); with Terracotta Vase, 3rd-2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)Born in Sicily, the ancient Greek historian Timaeus was forced to flee to Athens where he studied under the philosopher Isocrates. His greatest work, The Histories, spanned an estimated 40 books. It focused primarily on Greece, but also discussed events in Magna Graecia (Italy & Sicily); and it covered the earliest history of Greece to the time of the First Punic War. He worked diligently to develop a method of reckoning chronology based on the Olympiad cycle, the Archons of Athens, Ephors of Sparta, and priestesses of Argos which was used by many other historians.

Timaeus’ work circulated widely during Antiquity and was utilized by many other historians. He was, however, criticized by later historians, such as Polybius, for being unfair towards his predecessors, showing bias towards his subjects, being an armchair researcher, obsessing over trivial matters, and a general frigidity. On the other hand others, like Cicero, praised his work. Today only fragments of the 38th book of his Histories, and a reworking of its last section On Pyrrhus have survived; along with a reference to a history of the cities and kings of Syria, and The Victors at Olympia, a chronological piece that probably functioned as an appendix.

The Later Ancient Greek Historians

Phylarchus (3rd Century BC) Copper Coin of Pyrrhus of Epirus, 295-72 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver Tetradrachm of Cleomenes III of Sparta, 227-22 BC, via Alpha Bank Culture (right)

Copper Coin of Pyrrhus of Epirus, 295-72 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver Tetradrachm of Cleomenes III of Sparta, 227-22 BC, via Alpha Bank Culture (right)

Copper Coin of Pyrrhus of Epirus, 295-72 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver Tetradrachm of Cleomenes III of Sparta, 227-22 BC, via Alpha Bank Culture (right)

Copper Coin of Pyrrhus of Epirus, 295-72 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Silver Tetradrachm of Cleomenes III of Sparta, 227-22 BC, via Alpha Bank Culture (right)Three different cities are given as the birthplace of the ancient Greek historian Phylarchus; Athens and Sicyon in Greece and Naucratis in Egypt. His greatest work, The Histories, spanned an estimated 28 books. It is known to have covered a 52 year period beginning with Pyrrhus of Epirus (272 BC) and ending with the death of Cleomenes III of Sparta (220BC); though based on fragments it may have actually begun with the death of Alexander the Great. Phylarchus described events in Greece, Macedonia, Egypt, Cyrene, and elsewhere.

Much of what we know of Phylarchus as a historian comes from criticisms that were leveled against him. Polybius and much later Plutarch charge him with bias and falsifying history through partiality. He was also accused of trying to sway readers through his overly graphic descriptions of war and violence. Nonetheless, many ancient historians borrowed from his work. His works are known to include the Histories, The story of Antiochus and Eumenes of Pergamum which described a war between monarchs, Epitome of myth on the apparition of Zeus, On Discoveries, Digressions, and Agrapha which probably dealt with obscure mythological aspects.

Polybius (c. 200-118 BC) A Difficult Passage by Clarkson Stanfield, 1793-1867, via The British Museum, London (left); with Excerpts from Polybius’ Histories, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)

A Difficult Passage by Clarkson Stanfield, 1793-1867, via The British Museum, London (left); with Excerpts from Polybius’ Histories, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)

A Difficult Passage by Clarkson Stanfield, 1793-1867, via The British Museum, London (left); with Excerpts from Polybius’ Histories, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)

A Difficult Passage by Clarkson Stanfield, 1793-1867, via The British Museum, London (left); with Excerpts from Polybius’ Histories, 15th century, via The British Library, London (right)Polybius was born into a prominent family from the city of Megalopolis in Greece. He was an active member of the Achaean League before he was taken to Rome as a hostage. Whilst in Rome, Polybius was able to gain entry into the most elite social circles where he made many friends and contacts. As a result, he was able to witness and participate in many of the most important political events of the period; even accompanying and advising his Roman friends on military expeditions.

With his unparalleled access, Polybius was able to write a number of historical works, the most important of which was the Histories. Originally spanning some 40 books, today only 5 exist in their entirety. The Histories cover the period of 264-146 BC and mainly focus on Rome’s rise as a world power and its conflict with Carthage. Polybius also wrote several other works, which are now lost, and is considered one of the founding fathers of Roman historiography. His works were widely utilized by later historians, though he was often criticized for his dense writing style.

Agatharchides (2nd Century BC) Egyptian Writing Tablet, 332-31 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Pottery Jar lid showing four fish, 3rd-1st century BC, via The British Museum, London (right)

Egyptian Writing Tablet, 332-31 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Pottery Jar lid showing four fish, 3rd-1st century BC, via The British Museum, London (right)

Egyptian Writing Tablet, 332-31 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Pottery Jar lid showing four fish, 3rd-1st century BC, via The British Museum, London (right)

Egyptian Writing Tablet, 332-31 BC, via The British Museum, London (left); with Pottery Jar lid showing four fish, 3rd-1st century BC, via The British Museum, London (right)Agatharchides was born in Cnidus, a Carian city in Western Anatolia, he appears to have been a sort of assistant of servile origin. His major work is On the Erythraean Sea (Red Sea), which besides providing historical, geographical, and anthropological details about the region, advocates for a military invasion from Ptolemaic Egypt. The work was never finished as a rebellion or purge prevented Agatharchides from accessing official records in Alexandria.

On the Erythraean Sea spanned 5 books, of which almost the entire fifth book has survived. Agatharchides was praised for his clear, dignified writing style so that his work saw continued use even when it was superseded by more up to date material. It was quoted by numerous later historians such as Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, Aelian, and Josephus. Agatharchides also wrote other works, Affairs in Asia (10 Books) and Affairs in Europe (49 Books), which were not widely known and only survive as fragments.

Posidonius (c.135-51 BC) Roman Statue of a Wounded Gaul, 200 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (left); with Celtic Belt Clasp, 2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Roman Statue of a Wounded Gaul, 200 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (left); with Celtic Belt Clasp, 2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Roman Statue of a Wounded Gaul, 200 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (left); with Celtic Belt Clasp, 2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)

Roman Statue of a Wounded Gaul, 200 BC, via Musée du Louvre, Paris (left); with Celtic Belt Clasp, 2nd century BC, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (right)Nicknamed “the Athlete” as a result of his intellectual prowess in many fields, Posidonius was considered the greatest polymath of his age. Born in the Hellenistic city of Apamea in Syria, he was educated in Athens and traveled across the Mediterranean World. His travel brought his to Greece, Hispania, Italy, Sicily, Dalmatia, Gaul, Liguria, North Africa, and the Adriatic Coast. His historical work the Histories, continued where Polybius’ world history left off; covering the period of 146-88BC, it supposedly spanned 52 books. Today, almost all of Posidonius’ Histories have been lost.

The Histories of Posidonius continued the narrative of Roman expansion and dominance, begun by Polybius. Yet although Posidonius, like Polybius, was sympathetic to Rome he viewed historical events through a more psychological lens. He saw and understood human passions and follies but did not pardon or excuse them in his writings. As a result of his philosophical training, Posidonius also considered environmental or climatic factors, which he believed influenced how people acted or behaved.

Diodorus Siculus (c. 90-30 BC) The Abduction of Helen by Italian Giuseppe Salviati, mid 16th century, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Abduction of Helen by Italian Giuseppe Salviati, mid 16th century, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Abduction of Helen by Italian Giuseppe Salviati, mid 16th century, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Abduction of Helen by Italian Giuseppe Salviati, mid 16th century, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkDiodorus Siculus was a Greek from the city of Agyrium in Sicily, almost nothing else is known about his life. His great historical work was the Bibliotheca Historica or Historical Library. This was an immense work that originally spanned some 40 books. To complete this epic work, Diodorus Siculus drew upon the research of numerous earlier historians. However, much of the Bibliotheca Historica has been lost to time, so that only books 1-5 and 11-20 survive; along with some fragments and quotations preserved in the works of later historians.

Julius Caesar by Italian Andrea di Pietro di Marco Ferrucci, 1512-14, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Julius Caesar by Italian Andrea di Pietro di Marco Ferrucci, 1512-14, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Bibliotheca Historica was intended to be a universal history; that is it attempted to present the history of all mankind in a single coherent unit. As such, it was divided into three parts. The first section dealt with mythic history up to the destruction of Troy. The second and third sections covered the periods between the destruction of Troy and the death of Alexander, and from the death of Alexander to the beginning of Caesar’s Gallic Wars. Geographically, his work spanned the known world and included Egypt, India, Arabia, Scythia, Mesopotamia, North Africa, Nubia, and Europe.

Legacy Of Ancient Greek Historians

Although they lived thousands of years ago, ancient Greek historians have left a lasting mark on modern western society. From the ancient Homeric epic came the modern journey of the hero, and from the documentation of ancient warfare, historians have been able to study the military conquests of Antiquity and develop modern war tactics. The documentation of judicial, political, militaristic, cultural and artistic history in Antiquity has had an incalculable impact on modern western culture. Without the contributions of these ancient Greek historians, our world would look very different.

Robert Holmes has an MA in Ancient & Medieval History and a BA in Archaeology. He is an independent historian and author, who specializes in the Military History of the Ancient and Medieval World and has published over a dozen articles on related topics. Originally from Massachusetts, he now lives in Florida where he works doing public history leading tours, giving lectures, and educating people about the local history.

sâmbătă, 26 decembrie 2020

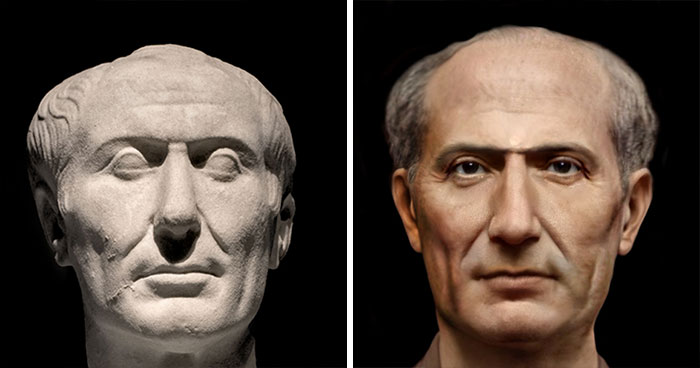

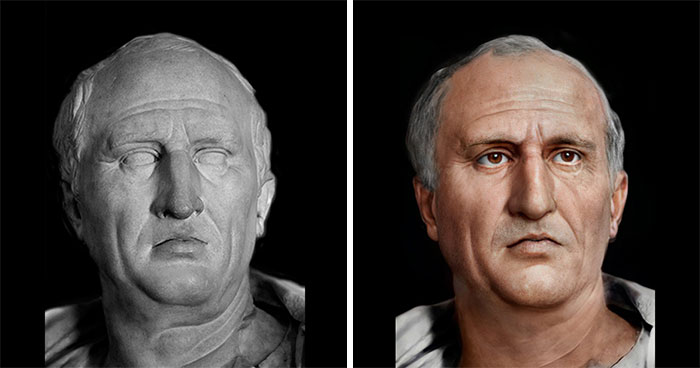

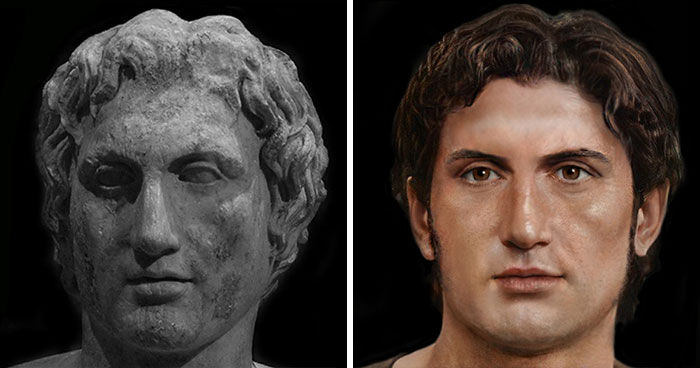

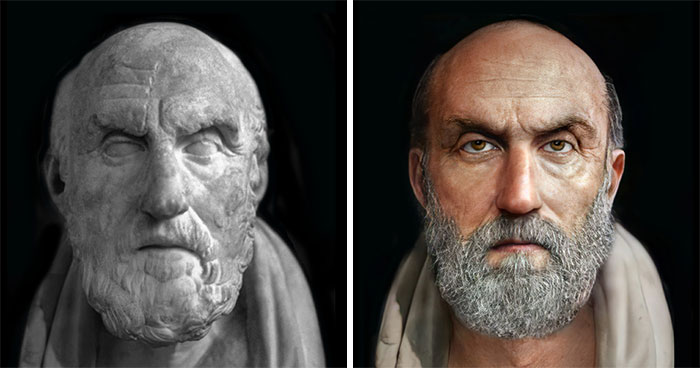

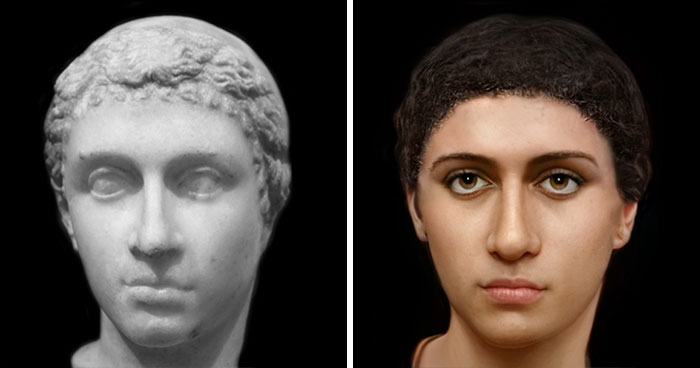

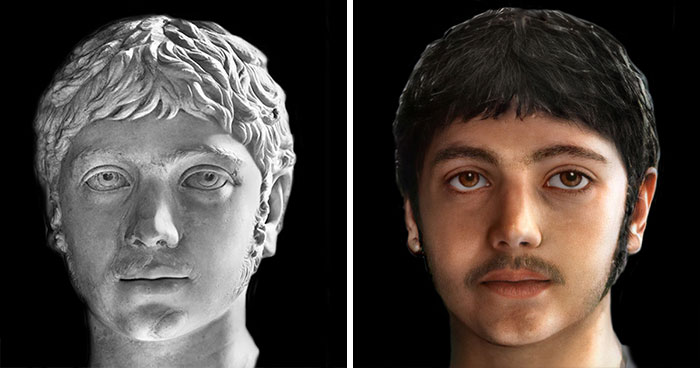

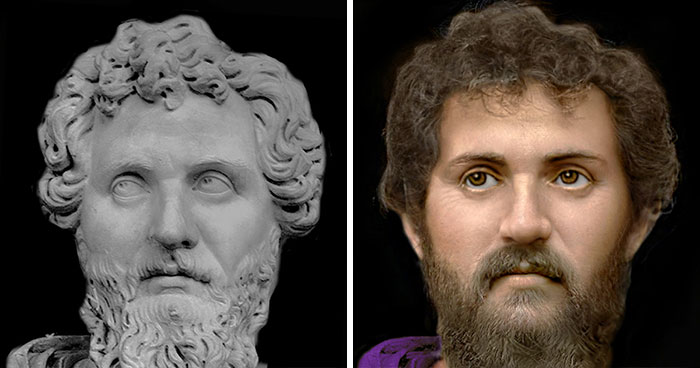

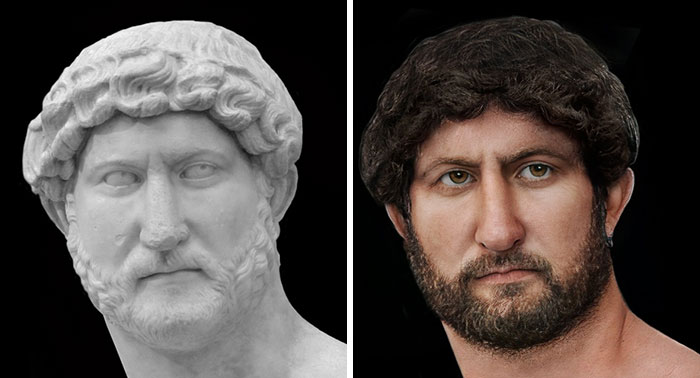

Roma / Grecia / CHIPURI ANTICE 2

#1

Roman General And Statesman Julius Caesar

#5

Roman Statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero

#6

Carthaginian General And Statesman Hannibal Barca

#7

King Of Macedon Alexander The Great

#10

Greek Stoic Philosopher Chrysippus Of Soli

#12 Greek Philosopher Antisthenes

# 16 CLEOPATRA

#18

Roman Emperor Elagabalus

#19

Greco-Phoenician Philosopher Zeno Of Citium

#23

Roman Emperor Septimius Severus

Abonați-vă la:

Comentarii (Atom)

-

Octavien, connu sous le nom d' Auguste . Ce titre, Augustus, est accordé par le Sénat romain le 16 janvier 27 av. J.-C. à Octavien (63 a...

-

ISTORICI GRECI DIN ANTICHITATE Herodot (484 BC - 425 BC ) Fragment d'Hérodote, papyrus d...

-

#1 Roman General And Statesman Julius Caesar #5 Roman Statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero #6 Carthaginian General And Statesman Hannibal Ba...

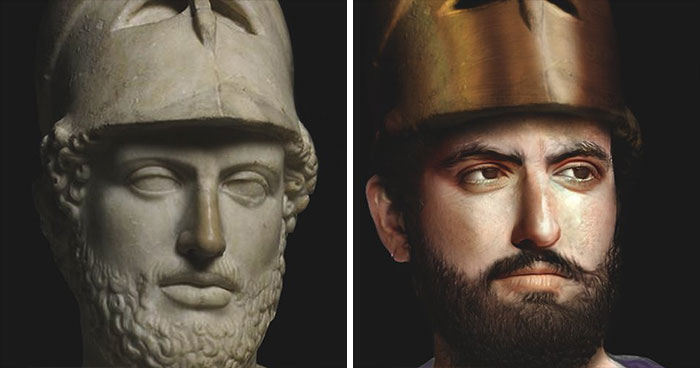

Greek Statesmen, Orator And General Pericles